Codesign with community: spotting codesign-washing

Codesign – from housing to streetscapes, everywhere we’re hearing officials say “codesigning with community”. But like any well-intentioned thing it’s become bastardised and buzzwordy, so how do we spot tokenism at 50 paces?

This is the first of the Dispatches from the Frontlines, a series on Linkedn about tactical urbanism.

Participatory practices are incredibly powerful, a core tenet of tactical urbanism, and it’s great to see this kaupapa coming through in the Innovating Streets programme. But fair warning: sprinkling nice participatory-sounding words around a tactical urbanism project, without the underlying integrity, can end up being worse than just doing a traditional (fraught) consultation process. So how do we spot “codesign-washing” – including in our own projects?

Words, schmerds… but integrity does matter

Tactical urbanism is grounded in a participatory philosophy of street change.

One participatory technique – codesign – is showing up in many new handbooks and guides (including Waka Kotahi’s draft Tactical Urbanism Handbook). And codesign has become a buzzword, throughout the public and private sector.

It’s become a label alongside other good-hearted but slippery phrases such as “to work with partners”, “to partner”, “work alongside”, “co-create”, but also “engage” and “involve”. It’s often hard to see whether there’s an actual relationship attached to the word that appears in a project plan, gets in lights in a report heading, or is heard in a workshop assuring Local Board members or councillors. And codesign is no different.

But let’s remember that like every important progressive concept (“green” / “sustainable” / “agile” etc etc), codesign’s buzzy popularity and inevitable bastardisation doesn’t negate a solid heart.

Participatory design (originally co-operative design, now often co–design) is an approach to design attempting to actively involve all stakeholders (e.g. employees, partners, customers, citizens, end users) in the design process to help ensure the result meets their needs and is usable.

Wikipedia

Integrity: it’s in the balance of power

Whatever name you call it, a successful tactical urbanism project needs the “community” to have much more influence on the project, relative to “experts”, than we find in normal projects.

In other words, where there’s integrity in a project’s participatory kaupapa – which is a major success factor – you’ll find the community players having much more constructive power, much earlier in the project, than we experts are used to giving them.

At the heart of every successful tactical urbanism project is a design process that feels strongly participatory especially for those with less power: those who aren’t in The Establishment, in council, or government, or expert consultancies.

[Hopefully we all know by now why it’s good to have higher-quality participation by regular people in things that affect them… see the IAP2 or in short: better-quality decisions, better supported by those they’ll affect, and stronger civics.]

Ultimately what matters is the genuineness and the actual relationships. You’ll be roughly right if you stay true to a good process (like that in Small Change Big Impact, or “Participation via communication and engagement” in Waka Kotahi’s Tactical Urbanism Handbook), and when asking yourselves “have we done enough, is this about right?” you keep putting yourself in your stakeholders’ and partners’ shoes (or better still, you ask them).

Codesign integrity: our process must match our words

But even with good intentions and good relationships we can definitely create a rod for our backs by using words that invoke expectations in people that we can’t (or won’t) meet.

And inevitably, this window-dressing, tokenism and “washing” of processes (greenwashing, agile-washing, and co-design-washing) causes a project a world of pain short- and medium-term.

If you follow a genuinely participatory process, which ideally is true to the kaupapa of codesign, you’ll not only have a slightly better set of transformations to the street. Crucially, in the wider public, your project will have a critical mass of people regarding it with curiosity, tolerance, and trust – and that’s gold. That’s your viable social licence to operate.

But if you “codesign-wash”, people’s disappointed expectations will embitter their attitudes to the project. Politicians, in particular, will double down on their democratic obligations to “defend the community against your project”. Community actors’ trust will be weakened, and their willingness to put in thousands of hours of mahi working with your organisation.

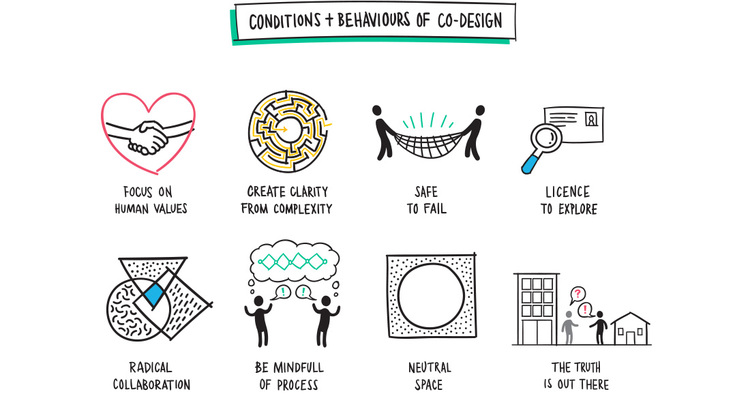

Codesign is a thing. It’s simple: just don’t use the word if you’re not intending to design something alongside the people who will use it, honouring the community players’ specialist expertise alongside your specialist expertise.* (Or, at the very least, look plausibly like you’re making a genuine effort to do so.) Here’s Lifehack’s great and widely-used outline of the basics of a codesign process.

Spotting codesign-wash at 50 paces

So how do we spot codesign-wash in this new territory of tactical urbanism? As you go along, or do your backcasting, it’s worth a “sniff test” of your project at 50 paces for the whiff of codesign-wash. Here’s a necessarily incomplete list of tips…

It’s time to do your first major public-facing comms. Is someone with a strong reputation in the local community willing to stand up and be photographed and quoted in the local paper, radio and TV comms with you?

- This is a good acid test because It doesn’t matter if you’ve done heaps of background work with genuine codesign intention (see the great process in “how we got here”). If you can’t announce it jointly with that someone, it won’t count for anything in terms of the public social licence to operate.

- Top tip: a councillor or senior officer announcing something in a council media release isn’t enough.

- Organisational champions like senior officers are a necessary pillar of the backstage structure, but nobody in the public really cares – they just expect you not to have wasteful inter-organisational bickering.

- Elected representative champions are necessary pillars of both backstage and public-facing structure, but they too are necessary but not sufficient. Especially look out if only the portfolio councillor is willing to stand up and be photographed, but the local / ward councillor has dodged.

Here are some other ways to “sniff test” for the whiff of codesign-wash:

- Are your technical experts in high-performing streets or public realm perpetually feeling like the project’s given the community partners a wee bit too much influence? That’s a good sign.

- As an experienced project manager, are you raising your eyebrows at the amount of early-stage time you’re paying for staff doing “backstage” sitting down and listening / talking with people you’d normally consider just “the public”, or “fringe users”, instead of “affected residents”? That’s a good sign.

- As lead of project comms, are you feeling slightly miffed at how a community partner is stealing your organisations’ thunder and talking proudly about the project as if it’s theirs and your organisation has just coat-tailed or come in subserviently to support it? That’s a good sign.

- As project manager, have you created a comprehensive design plan with your expert consultants, and reached out to the same “representative stakeholders” as your last project to do a “codesign workshop”? That’s a bad sign.

- When you’ve installed the street improvements, and you’ve realised a major design boo-boo (e.g. road-crossing pedestrians waiting in the tactical cycle/micromobility lane), are you uncomfortable tweaking anything? That’s a really bad sign. (And it’s too late by then to retrospectively fix your project’s poor participatory integrity, so just own it, do damage control, and move on swiftly with something positive that takes the bitter taste away for people.)

I’ve sniffed but I’m not sure…

If you’re not sure, err on the side of assuming you haven’t done thoroughly participatory co-design, and don’t go around talking or acting like you have. Instead, be honest that you’ve slightly improved on normal processes – people will respect the honesty.

And in the meantime, go back and invest in your relationships and in thoughtfully transferring some power (ideally real, but at least perceived) to your non-Establishment partners.

Questions? Comments? Profound disagreements? Bring ‘em on! Comment below.

*Community members’ expertise: in their lived experience of the street. Your specialist expertise: traffic engineering, urban design, etc.

Further reading:

- ThinkPlace codesigning quit-smoking programmes with wahine Māori

- Connect The Dots and allies’ codesign approach to reinvigorating a main street in Philadelphia

- Auckland Codesign Lab on the ethics of codesign (vid)

Next up: How do we do decent, authentic codesign – or participatory processes with integrity? Stay tuned for the next Dispatch from the Frontlines

Leave a comment