Eco-City done well could solve housing crisis. Part two of three.

In part two of three, guest poster Harre dishes up possibilities for the proposed Wellington Eco-City, how housing could be integrated with rapid transit and how houses can be built affordably.

This appeared in Harre’s collection of essays on Medium,”New Zealand needs an urbanisation project”, and is republished here with permission. Catch up on part one here.

The Eco-City proposal – Integrating housing with rapid transit

Lincolnshire Farm could be developed as a transit oriented ‘Eco-City’. This would allow for new housing typologies to significantly increase housing density.

The Eco-City could take learnings from HLC for what kinds of higher density housing typologies would be commercially viable.

“In 2012 we built the first terraced homes at Hobsonville Point. Our builder partners and the general market told us we were crazy and that the homes would never sell.. We sold this block before the were completed and within six months we were building the second block.”

Mark Fraser

This new type of housing development could have five times the floor space compared to a typical New Zealand suburb.

There would be more mixed use commercial and residential. Section sizes would be much smaller -about 200sqm on average and housing would be more ‘up’ than ‘out’.

This will alter Lincolnshire Farm’s predominant development type from greenfield to a new type of suburban development -integrated higher density housing with rapid transit.

The Lincolnshire Farm Eco-City could easily accommodate 25,000 people and 10,000 houses using an integrated housing with rapid transit developmental model. This would make the Eco-City the most responsive part of Wellington’s future housing supply.

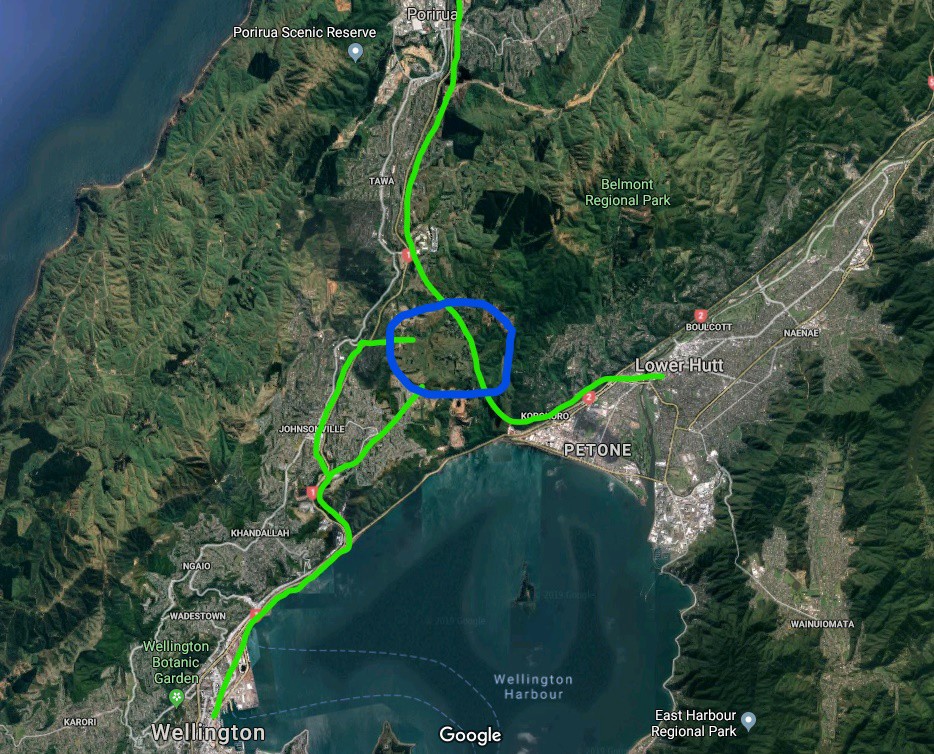

In my opinion the most feasible solution to providing the transport connection between Porirua and Lower Hutt would be to use bus rapid transit (with electric buses) and congestion road pricing. This would provide rapid transit connections to Wellington, Lower Hutt and Porirua from Lincolnshire Farm, with bus journey times well under 30 minutes in all directions.

The bus rapid transit routes would either use State Highway 1 or 2 or the yet to be constructed Petone to Grenada link road.

Congestion road pricing is an imperative part of this proposal, as it would ensure the motorway network is always free flowing so bus journeys are unimpeded even at peak times.

Road pricing would improve the efficiency of the motorway network as free flowing roads can carry more people than gridlocked roads. More generally, road pricing is an efficient way to allocate the scarce resource of urban road space. It avoids the productivity losses of excessive queuing.

Road pricing at peak travel times would encourage car drivers, especially single occupant car drivers, to use alternative routes, modes and times.

For popular high occupancy bus routes the congestion charge is spread over dozens of passengers, so the charge per passenger is minimal. Thus congestion charges would gently encourage the Wellington road network to carry more people with the same number of vehicles.

There are some inequality concerns regarding congestion road pricing for cities that have high automobile dependency and poor provision of alternative congestion free transport modes. In these cities congestion road pricing may not be an initial policy option because it could price low income people off road journeys -thus increasing inequality.

In New Zealand the inequality concerns of congestion road pricing could be true for Greater Christchurch because that city has an almost one for one automobile dependency ratio (909 light vehicles per 1000 people) and the wider City does not have a rapid transit network.

Neither of these facts are true for the Wellington region -which has a much lower automobile dependency ratio (647 light vehicles per 1000 people) because its commuter train network provides genuine multi-modal transport choices. This means congestion road pricing could be introduced immediately in Wellington without causing detrimental inequality effects. Especially as the proposal improves the wider rapid transit network by providing a faster Lower Hutt to Porirua public transport connection.

How to acquire affordable land?

What about the problem that Lincolnshire Farm is owned by Rodney Callender who seems to be in no hurry to develop it for residential housing?

This is where the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development’s -Housing and Urban Development Authority will be very useful.

New legislation establishing a Housing and Urban Development Authority will be introduced by Parliament this year to replace the previous government’s Special Housing Legislation which expires in September 2019.

The first Housing and Urban Development Authority projects are expected to be up and running in early 2020. These will be in Mangere, Mt Roskill and Porirua.

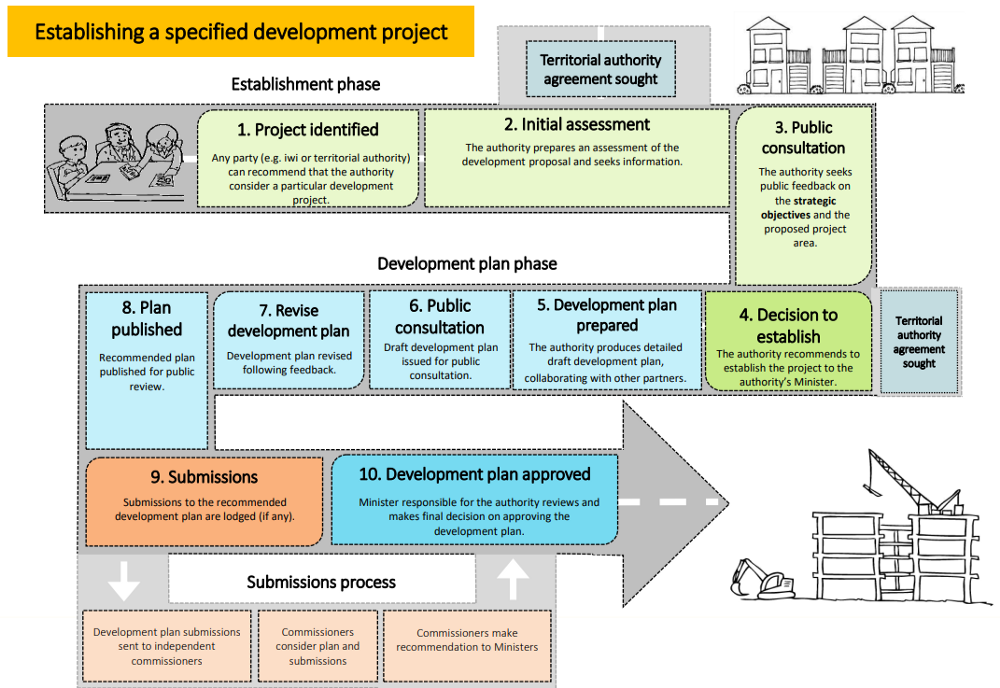

Process the newly formed Housing and Urban Development Authority will use to develop specific developmental projects

If the government wants to tackle the housing crisis in Wellington and elsewhere then they should quickly enact this legislation and progress through the establishing specific project stages. The year 2019 to 2020 should be the period that Wellington’s Eco-City is established as a specific project i.e. it goes from conception to starting construction by the end of 2020.

For the Eco-City proposal it would be in Rodney Callender’s best interests to cooperate with a shared equity process organised by the new Housing and Urban Development Authority. An example of shared equity is land readjustment which is a proven success overseas.

The Housing and Urban Development Authority in this case would be the organising agent whereby landowners, such as Rodney Callender exchange their larger blocks of land (Lincolnshire Farm) for more valuable yet smaller blocks of land.

Readjusted land for transit oriented development is more valuable because through a public process it is given residential zoning, it is fully serviced with streets, water mains, sewers, stormwater management systems, local parks and other amenities, it is within walkable distance of rapid transit and the land has been subdivided into multiple property titles.

The freed up land from land readjustment would go towards lowering the cost of public spaces -streets, parks, schools etc. And for social and affordable housing i.e. low cost land for State and Kiwibuild housing.

The transit provider -in this case the bus rapid transit entity could also get an allocation of lower cost land to build residential and commercial spaces. These rentals could help pay the ongoing operating costs of rapid transit.

This land readjustment system would have significant environmental and social benefits whilst also aligning the various stakeholders interests in ensuring the commercial success of the Eco-City.

For Rodney Callender the bottom line for his Lincolnshire Farm property is the Eco-City land readjustment option would quickly give him something like 2,500 property titles (versus Kiwibuild, HNZ and the Bus Rapid Transit provider getting 7,500 titles). It would be quick because the intent of the Housing and Urban Development Authority is to reduce development time from conception to starting construction down to as little as a year.

If Rodney Callender prefers to build another traditional subdivision like he has in nearby Churton Park, due to it being much lower density he would not create as many property titles. Also continuing to build traditional suburbia will not be as fast, as the housing only caters for the very small high end of the market where there is very little demand.

Going forward Rodney Callender should consider there is likely to be frustration and community objections to constructing suburbs that transport-wise are completely automobile dependent and that only cater for the needs of the highest income end of the property market. These community objections are likely to be reflected in increased planning restrictions or delayed public infrastructure provision.

Large Urban Development Authority projects have economies of scale with respect to development costs, meaning the Eco-City has the potential to have higher amenity provision for lower costs. Rodney Callender being a stakeholder partner with the Housing and Urban Development Authority would be one of the beneficiaries of these lower costs.

I believe the above facts indicate the most rationale course of action for land owners like Rodney Callender would be to cooperate with the Housing and Urban Development Authority to develop specific projects -in this case to develop Lincolnshire Farm into a Eco-City.

Can houses be built affordably?

The raw land costs for Kiwibuild, HNZ State houses and the Rapid Transit provider houses in this Eco-City proposal would be zero using the land readjustment option. In this case the land costs becomes the infrastructure costs of servicing the land.

Auckland Council economists estimate for their city infrastructure costs are $140,000 per developed section. Developers tell me the figure is about $90,000 but they do not include the big connecting transport infrastructure costs.

For Lincolnshire Farm implementing the Petone to Grenada link road with dedicated bus lanes for rapid transit might cost $500m (a feasibility study will give a more accurate figure), which divided by 10,000 houses is $50,000 each, that added to $90,000 also makes about $140,000.

I suspect an Urban Development Authority building at higher densities would have significant economies of scale, so the per section cost might be less. Alternatively the Development Authority may be able to provide better public amenities (for example a public library or swimming pool) for the same price.

The $140,000 land cost could be an upfront cost or it could be paid off over time by a targeted rate or fee. In which case it could pay off a municipal bond that is held by the Housing and Urban Development Authority -so not on local or central government balance sheets. This means local or central government debt limits will not restrict the provision of infrastructure for integrated housing and transport projects.

KiwiBuild prices need to be under $500,000 outside of Auckland.

Overseas it is quite easy to find newly built homes for well under $500,000.

Build prices for an Eco-City would need to be lower than Wellington’s current land and house build costs, so that the large number of houses -10,000 -can be sold to middle to low income buyers who have been priced out of the Wellington property market. If prices are too high there will be insufficient demand and the development will not be a commercial success.

When former Reserve Bank economist Michael Reddell first purchased his Wellington home in Island Bay 30 years ago the value of that house once inflation and income growth was accounted for is $400,000 in today’s money.

$400,000 is probably a reasonable target for affordable newly built housing in Wellington.

So as land costs could be about $140,000 then house building costs would need to be $260,000 to achieve affordable house pricing. Given modest sizes -say a maximum of 130 sqm and build costs of $2000 per sqm, this should be achievable. Especially as 10,000 houses will be built -so there would be large economies of scale for builders.

Prefabrication and house building factories may help to keep build costs down.

The country is getting closer to importing complete prefabricated houses, as well as seeing major local and overseas companies setting up giant house-building factories in New Zealand.

The icon of the Labour Party, Michael Joseph Savage, when attacked for building state houses in the face of the post-Depression housing crisis, said, ‘We do not claim perfection, but we do claim a considerable advance on what’s been done in the past’.

We can not yet claim a considerable advance but we are making steady progress.

We all know building our way out of the housing crisis was never going to be easy, or simple.

We always knew it would be tough to run up against 40-odd years of housing orthodoxy, and intervene in a broken housing market to deliver affordable homes and to turn around dwindling home ownership and the obviously sub-par quality of the country’s housing stock.

Twyford outlined the Government’s plan to create a Housing and Urban Development Authority by combining KiwiBuild, Housing New Zealand and the Hobsonville Land Company (now called HLC), which had successfully developed a former air force base on the outskirts of Auckland. He describes this new entity will have an end-to-end grip on planning for housing in New Zealand, giving it the ability to deliver large-scale development projects like Hobsonville Point. That

This all indicates he is expecting his new Housing and Urban Development Authority to be used for projects something like the proposed Wellington Eco-City development.

In part three, Harre will ask and answer – can the Eco-City be politically and economically viable?

Images

Feature, Hobsonville playspace – Isthmus

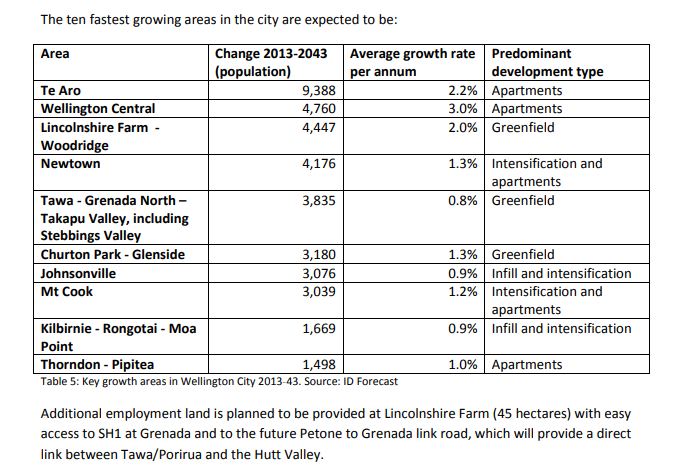

Table from ‘Let’s Get Wellington Moving Baseline report: Land use and urban form’, page 34

Google Map image with blue and green added by Harre

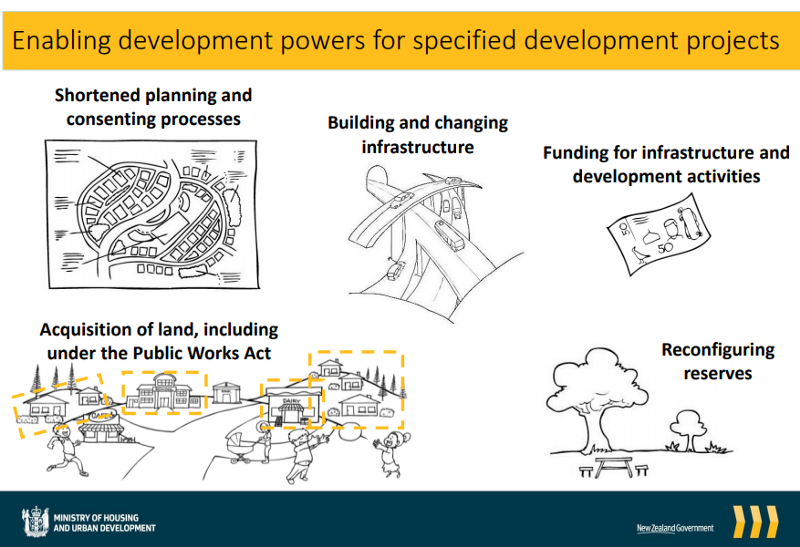

Process flow chart & graphic – Ministry of Housing and Urban Development

Small Home Lab Test – HLC slideshow

Leave a comment