“Of course it’s worth it, they’ve said we’ll save 25 minutes at peak”

Are our Business Cases Founded on a Lie?

Last year Matt wrote a post about NZTA’s Post-implementation reviews. These reviews are undertaken a few years after a transport infrastructure project is completed, and perform three functions:

- To see how the outcomes compare what was expected before the project was built

- To explain any variation in those measures

- To identify lessons that can be learned to improve other projects.

We have also written before about them here.

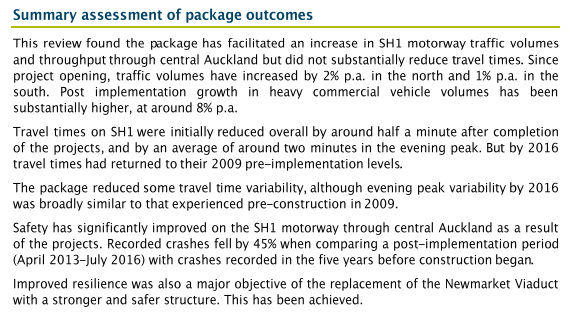

One example of an interesting finding, is from the post implementation review of the Victoria Park – Newmarket project, which is no longer generating any travel time savings. In fact, now travel times are worse.

This is a major problem because the biggest benefit in business cases for general traffic capacity projects is time travel savings. For some projects travel time savings make up nearly all of the benefit. If we are finding that projects are not resulting in these forecast travel time savings, then we need to be updating our models and our process for analysing projects.

These questions about travel time savings benefits have been around for a while. In a fairly ground-breaking 2008 paper, UK academic David Metz pointed out that while travel time savings benefits make up the vast majority of the expected benefits from road investment, actually average travel times are staying the same.

It should be possible to measure time saving if this is a significant part of the benefits to travellers of new investment in transport infrastructure. Travel time is measured in surveys of personal travel behaviour, typically using 7-day travel diaries. In Britain, for instance, average travel time (per person per year) has been reported since 1972/73 as one output of the National Travel Survey (NTS) (see most recently Department for Transport, 2006a). This household survey covers personal travel by residents of Britain along the public highway, by rail and by air within Britain, including walks of more than 50 yards. The most recent value of average travel time is 385 hours per person per year, or just over 1 hour per day. As indicated in Figure 1, this has changed rather little over 30 years, during which period car ownership has more than doubled and the average distance travelled has increased by 60%.

It seems as though this trend is also true in New Zealand, with changes in travel time per person over time mainly being due to modal shift (we walk less than we used to) rather than any actual decrease in overall time:

Metz points out that we should be surprised by these results, given the great promises of travel time savings in the business cases for all the transport investment we have been making:

These data on average travel time offer no obvious support to the idea that travel time savings comprise the dominant element of the benefits from investment in the transport system. Indeed, Figure 1 prompts the following question. What has happened to all the travel time savings claimed to justify public expenditure on British roads of around £100 billion over the past 20 years at current prices? One possible answer would be that had it not been for the time savings associated with this investment, average travel time would have been higher than it has been. The pattern of investment in road infrastructure in Britain over the past 20 years has shown marked swings in expenditure, between £3.5 and £6.4 billion per year (at constant 2004/05 prices) (Department for Transport, 2007) and, hence, in new capacity becoming available. The steady trend of travel time seen in Figure 1 shows no suggestion of a reflection of such variation in new capacity, and hence offers no support for the idea that average travel time would have been higher in the absence of new road construction.

An alternative interpretation of Figure 1 is that people take the benefit of investment in the transport system—private investment in vehicles as well as public investment in infrastructure—in the form of additional access to desirable destinations, made possible by higher speeds in the time available for travel. From this viewpoint travel time savings would be at best transient phenomena. Light might be shed on this possibility by empirical studies of travel time savings putatively associated with infrastructure investment, such as a new or widened road that has been built with the intention of generating such savings.

It is this important distinction between “saved time” and “better access” that sits at the heart of our need to update business case processes to actually match with the real impact of investment. While the two seem similar, there are many ways of improving access that don’t require building new roads – things like better land use policies that allow housing to be built in areas that already have a lot of access. Or investment in public transport improvements that improve the access of an area in a way that can be maintained over time and doesn’t get eaten away by induced demand.

Our strategy documents have caught up with this new paradigm. ATAP, the GPS and the Auckland Plan all emphasise the importance of accessibility. But the cost-benefit analysis process still lags behind with its outdated focus on travel time savings. This means we are continuing to have a situation where roading projects appear to score decent BCRs even though they will almost certainly not deliver long-lasting gains. Getting past this will require an acceptance of two key points:

- Increasing general traffic capacity does not result in beyond short-term travel time savings (due to induced demand);

- Many people will bank the time savings and simply travel further (known as the Marchetti Constant);

If we are to build the right projects we need to ask the right questions and update the way we measure benefits of transport investment. At the moment we are still asking the wrong questions when doing this analysis, which is going to undermine the efforts of our strategic documents to focus more on projects that generate long-lasting accessibility gains.

The big, expensive transport projects in the Wellington Region are overwhelmingly justified because they’re supposed to give us time benefits – the business cases stack up. That’s the case for all the expressways in Kāpiti, Ōtaki, the Smart Motorway in Wellington (more reliable travel times, and note this), and is the logic behind the “we need bigger roads first” arguments around Let’s Get Wellington Moving.

We’ve believed faithfully in the value of time as given to us (at great expense) by investments based on orthodox business cases.

Is it time to start checking our sums?

Leave a comment